England Turns to a German to Manage Their National Football Team

As of January 1, the highly esteemed position in the national football scene will now be held by a German. The Football Association, the governing body of England's national sport, officially announced on October 16 that Thomas Tuchel has signed a contract to lead the Three Lions until the conclusion of the 2026 World Cup.

The sporting logic behind the appointment of the 51-year-old Tuchel is impeccable. He has coached several of the world’s most prominent clubs, including Borussia Dortmund, Paris Saint-Germain, Bayern Munich and Chelsea. He has won domestic honours in both France and Germany, and lifted the Champions League trophy with English Premier side Chelsea in 2021.

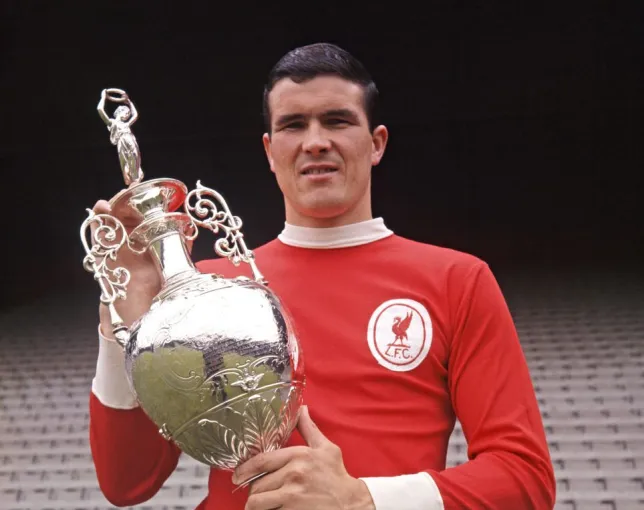

He is, as the FA said in a statement, “one of the best coaches in the world,” an ideal candidate to salve English football’s open wound: the fact that it has not won a major men’s tournament since 1966.

But despite his heavyweight resume, Tuchel’s appointment has not met with universal approval. The right-leaning Daily Mail described his arrival as a “dark day for England” on the morning of Oct 16.

The tabloid placed particular emphasis on the fact that the country had hired not just a foreigner but someone from Germany: traditionally one of England’s great rivals, both sporting and otherwise. The word “German” was in all capital letters on the newspaper’s back page on Oct 16.

The FA has been searching for a permanent coach for its men’s team since the previous incumbent, Gareth Southgate, resigned in July, only a few days after England lost in the final of the European Championship. The FA confirmed it had considered as many as 10 prospective replacements, some of them English, before selecting Tuchel.

“Fundamentally we wanted to hire a coaching team to give us the best possible chance of winning a major tournament, and we believe they will do just that,” Mark Bullingham, CEO of the FA, said in a statement.

“Thomas and the team have a single-minded focus on giving us the best possible chance to win the World Cup in 2026.”

The rules of international football dictate that teams must comprise players eligible to represent each country, whether that is through birth, ancestry or naturalisation. That principle, though, does not extend to coaches.

It is not especially unusual for countries to import candidates to guide their national teams. Portugal’s current coach is Spanish. Austria’s is German. Of the 10 countries currently trying to qualify for the World Cup in South America, seven are led by Argentinians. One of them recently took charge of the United States men’s national team. The US women’s side is led by Emma Hayes, an Englishwoman.

But the majority of the most powerful countries in men’s football – the ones who enter continental championships and the World Cup with not just ambitions of victory but expectations of it – have not taken the step in the modern era, preferring instead to see their national teams as an expression of the strength of their national football culture.

England are very much the exception: Tuchel is the third foreign hire to lead their men’s team. Both previous appointments – Sven-Goran Eriksson, a Swede who arrived in 2001, and Fabio Capello, an Italian who took charge six years later – were justified as the only way to deliver a trophy. Both were criticized in some quarters at the time. Neither delivered the silverware expected of them.

Sam Allardyce, who endured a brief, controversial spell as England manager in 2016, called the appointment “disappointing.” Harry Redknapp, an experienced and widely popular coach at club level, admitted he wanted “an Englishman to manage England.”

“I’m very patriotic. I think we should have an English manager,” he said.

That sentiment is likely to be shared by at least a portion of England’s fans. During the European Championship in Germany last summer, England fans were requested by police not to sing “Ten German Bombers,” a chant celebrating the Battle of Britain in World War II that is regarded as “discriminatory or disrespectful” by both the FA and Uefa, European football’s governing body.

Three years before that, fans were warned they would be banned from attending games if they sang it before the clash between England and Germany.

At a time when England is reckoning with an ascendant populist right which claims to be defending English national identity, though, Tuchel’s appointment may be more contentious still.

“Why can’t we have an English manager?” asked Nigel Farage, the hard-right lawmaker and leader of an anti-immigrant party that secured some 4 million votes in Britain’s general election in July.

On Oct 16, at his first public appearance since accepting the role, Tuchel – speaking flawless English – acknowledged the complexity of his position, but stressed the affection he feels for England in general and English football in particular.

“It’s the biggest job in world football,” he told a hastily assembled news conference at Wembley, England’s national stadium.

“I am sorry that I have a German passport, but I give the greatest respect to the country. Maybe people will remember my passion for English football, my passion for living here.”

After being fired by Chelsea in 2022, he said, he had “always wanted to return to England. It’s here that I have the best memories. I know there are some trophies missing. I want to help to make it happen.”

He admitted, though, that he had not yet decided whether he would sing the national anthem before games, a long-standing and slightly bizarre obsession of the British tabloid media.

Lee Carsley, a youth team coach with Irish roots who had been acting as interim manager while the FA made its appointment, had said he would not sing the anthem before a game in Dublin in September and was pilloried for his stance. During his tenure, Capello had said he felt it was “wrong to sing another country’s anthem”.

“I have not made my decision yet. Your anthem is very moving. I will always show my respect to the country. But I will take my time,” Tuchel said.

As he makes his choice, he might take into consideration the fact that “God Save The King” is about the preservation of another high-pressure job in English public life that was, at one point, outsourced to a German. NYTIMES

RELATED STORIES

LATEST NEWS